Concord Elementary School

Contents

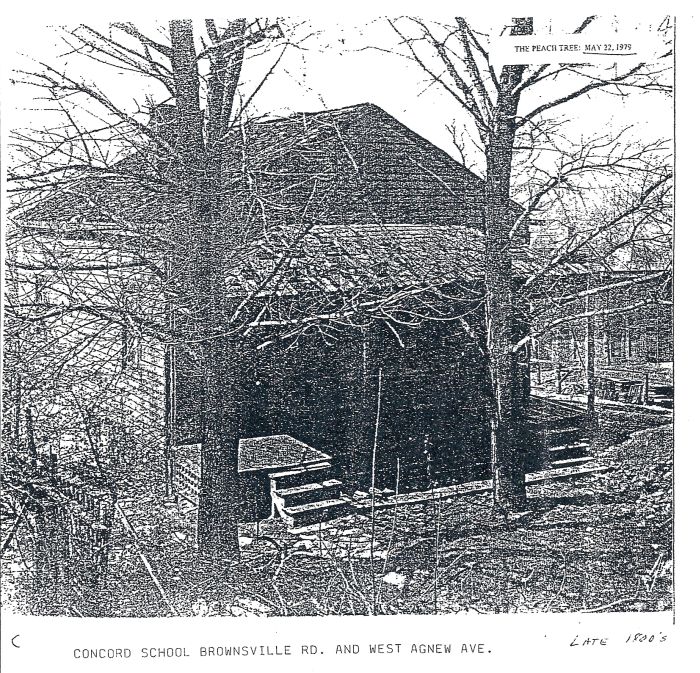

- 1 Photo of the second location of Concord Elementary School located at the corner of current Brownsville Road and West Agnew Avenue.

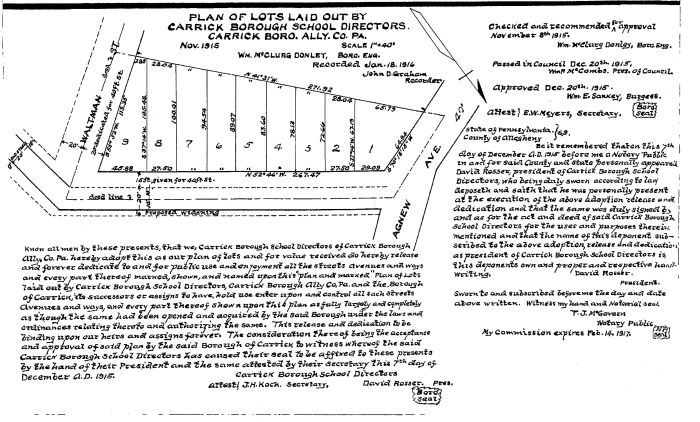

- 2 After the Carrick school board built the fourth location of the Concord Elementary School the land that the third school was located was divided into lots. Here is the plan of lots on what is Dowling Street between Hornaday Road and Agnew Avenue.

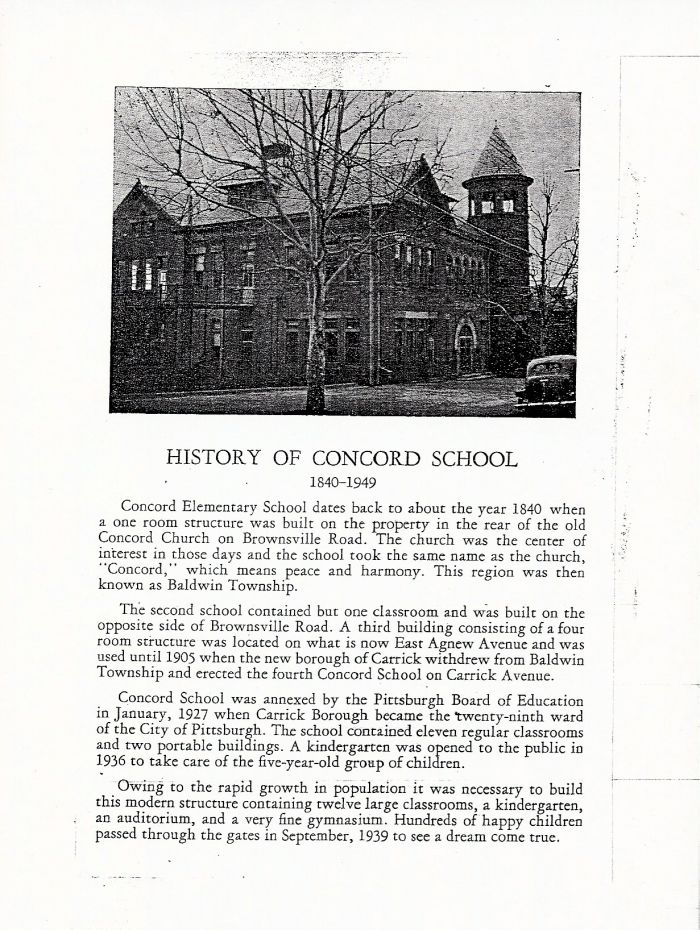

- 3 Photo of the fourth location of Concord Elementary School and a short history written in 1949 of the history of Concord Elementary School from 1840 to 1949.

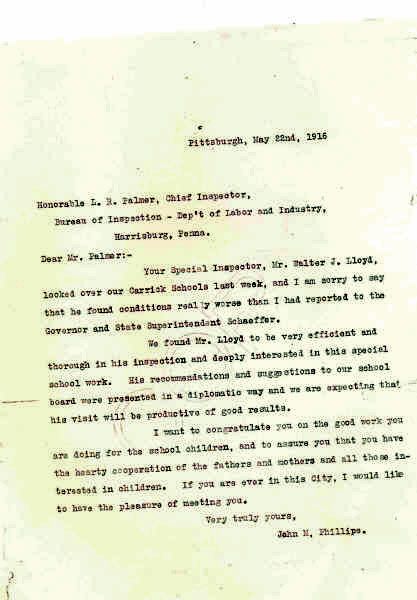

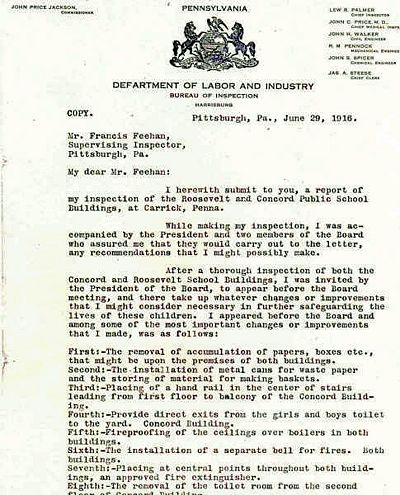

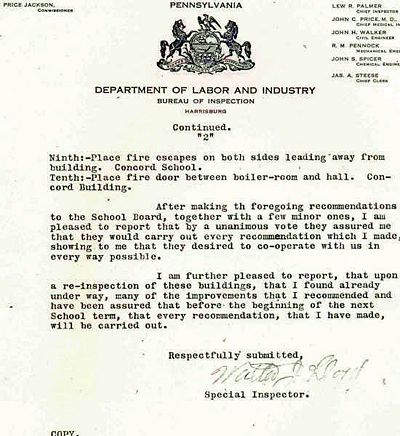

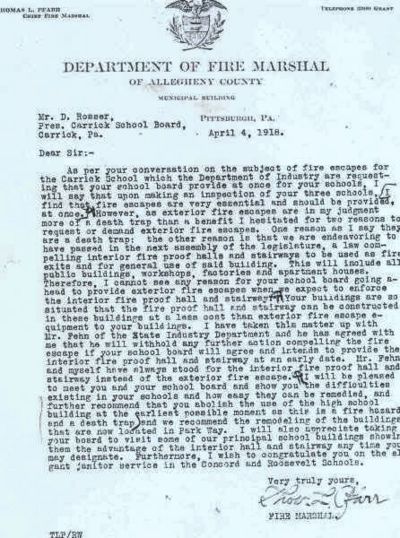

- 4 Many people questioned the reasoning of demolishing this, the fourth location of the Concord Elementary School. It appears in the photos to be a fine building but from these letters it may have been a fire trap.

- 5 Concord Elementary School 1906

- 6 This is a first hand actual story submitted Emily Pritchard Cary about going to school in the Concord Elementary School's fourth location on Carrick Avenue.

- 7 CONCORD SCHOOL

- 8 By Emily Pritchard Cary

- 9 Newspaper article about Concord students who were swindled.

- 10 Concord Students crossing the street - note no traffic signals, just a crossing policeman.

- 11 Concord Elementary School Library 1950

- 12 Concord Music 1960

- 13 School Web Site

- 14 This entry was posted on the Pittsburgh Board of Education web site on Friday, October 9th, 2009 at 3:51 pm and is filed under Good News, Pittsburgh Concord K-5, Pittsburgh Grandview K-5, Pittsburgh Roosevelt PreK-5.

- 15 Students of Pittsburgh Concord , Pittsburgh Roosevelt and Pittsburgh Grandview get a visit from author Betty Tatham

- 16 Concord Elementary students learn about Carrick history

Photo of the second location of Concord Elementary School located at the corner of current Brownsville Road and West Agnew Avenue.

After the Carrick school board built the fourth location of the Concord Elementary School the land that the third school was located was divided into lots. Here is the plan of lots on what is Dowling Street between Hornaday Road and Agnew Avenue.

Photo of the fourth location of Concord Elementary School and a short history written in 1949 of the history of Concord Elementary School from 1840 to 1949.

Many people questioned the reasoning of demolishing this, the fourth location of the Concord Elementary School. It appears in the photos to be a fine building but from these letters it may have been a fire trap.

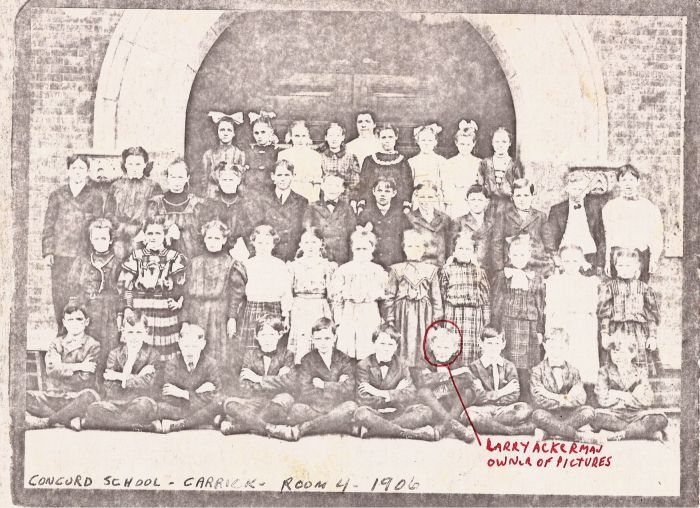

Concord Elementary School 1906

This is a first hand actual story submitted Emily Pritchard Cary about going to school in the Concord Elementary School's fourth location on Carrick Avenue.

CONCORD SCHOOL

By Emily Pritchard Cary

Quite by accident, I entered school long before Mother had planned to enroll me and subject me to the mercy of childhood germs. In addition to the prospect of contracting diseases, another deterrent was the dangerous traffic between our home on Madeline Street and the old Concord School located just off Pittsburgh’s busy Brownsville Road.

Mother took me along one morning when she visited Concord School to vote on a local issue. Bored with standing in line, I soon found my way into a nearby classroom. By the time my distraught mother, accompanied by the principal, located her errant daughter, I was seated in the midst of an advanced third grade reading group. As she entered the room, Mother heard the teacher promise her bewildered students that they could read as well as the little stranger if they applied themselves diligently.

Not wishing to interrupt, the principal hovered in the doorway while I reeled off several pages of the basal reader. “Mrs. Pritchard,” she cried at the end of the passage, “you simply must place your daughter in school!”

Mother was less enthusiastic. A fifth-grade teacher prior to marriage, she was thrilled to learn than Concord School had departmentalized classes, an innovation in elementary education fostered by Columbia University’s Horace Mann experimental school. This method advocated sending children to separate teachers for reading, math, social studies, and science, as well as music, art, and gym. She raved about the progressive Pittsburgh Public Schools and their venture in what was then the cutting edge. Still, she hesitated to put pressure on a child not yet old enough for kindergarten.

At length, the principal prevailed by appealing to Mother’s parental pride. Over the telephone, she made arrangements for us to visit the University of Pittsburgh, where an educational psychologist named Dr. Manwiller would give me a battery of tests.

Several days later, Mother and I traveled by trolley to an office in the university’s great Cathedral of Learning. “Some day, you’ll go to college here,” she promised.

I had no idea what that would entail, but I was receptive to visiting any institution that would allow me to read. I immediately warmed to Dr. Manwiller, who allowed me to read bits and pieces of amusing stories to my heart’s content. This was all part of his testing program.

Subsequently, as the result of my afternoon of pleasure, my future was sealed: I was admitted to the second grade in Concord School with few qualifications, except my ability to read and to dutifully follow my classmates in line as we marched from one classroom to another or to the second-floor library, my favorite location in the 19th century building that sported a bell tower. To begin with, I was exceedingly clumsy. I struggled to get myself in and out of coats, hats, boots, leggings, and all the trappings Mother insisted that I wear even in warm weather. My parents lost their first child two years before my arrival and were bent on doing everything in their power to keep me alive, no matter that it caused my discomfort.

Gilda Minetti came to my rescue. She was large and motherly and wore shoes that clicked on the bare classroom floors when she walked. Her ears were pierced by gold rings that sparkled, even under the classroom lights on gray, smoggy days. When she buttoned me into my coat and shoved my feet into stiff boots each afternoon, I wanted to hug her.

Ruth Kirshner sat beside me. Exceedingly personable, she smiled a great deal and was singled out by the teacher to recite in an assembly program. I remember that the teacher coached her to pretend she was the baby bird in the story. In a sing-song voice Ruth incorporated dramatic flourishes as she recited, “My mother, I know, would sorrow so, if I were taken away.”

As her closing lines faded away, the parents in the packed audience applauded her heartily, no doubt responding to the fears kindled several years earlier by the notorious Lindbergh kidnapping. I would have given my waist-length braids to be as cunningly cute as Ruth.

Donald Kirshbaum sat behind Ruth. He had freckles, a pixie face, and a flair for drawing. Early in my school career, he rescued me from disgrace during a social studies class.

To illustrate a unit on farms, our teacher conceived the notion of sending each student to the blackboard to draw a farm animal. After instructing us to raise a hand when we heard our favorite, she read off the list of creatures she wanted reproduced.

Pig, goat, cow, chicken... each sounded more difficult to me than the one before. By the time the teacher reached the last animal on her list, everyone else in the class had selected one. I began to relax, believing that she had forgotten me, and was about to rejoice inwardly when she moved down the aisle and thrust her finger in my face.

The parted lips before me revealed gold-capped molars. What she may have believed to be a warm, friendly smile, I interpreted as a sinister sneer. My heart pounded as she said, “Emily, you haven’t selected an animal yet, so I’m going to let you draw the horse. I think it’s everyone’s favorite.”

Shakily, I made my way to the chalkboard and began to construct a body of circles. They did not work. Next, I tried squares. Then ovals. They looked slightly more horse-shaped, but the sticks I added for legs were ludicrous. I was fast approaching tears when Donald reached out from his desk next to the blackboard. With a few deft strokes, he transformed my mess into a masterpiece.

While this was going on, the teacher stood with her back to me busily observing another student’s work. Upon pivoting around and viewing the drawing, she appeared to be stunned, but quickly recovered and announced to the class, “Emily’s drawing is very realistic.” If the other students knew the secret of my success, they never let on.

One of my new friends was Lois Geib. Blonde and merry, she invited me to her house, where we played with dolls and sampled delicacies baked by her grandmother, a native of Germany. Several summers later, Lois, her grandmother, and her parents traveled to Germany for what was to have been a brief visit with relatives. Hitler was in power. The war commenced; they never returned.

After Lois’ disappearance, Janet Cready, a chubby blond with a boyish bob, became my frequent companion. She shared my joy of reading, and we vied to consume all the mystery books in the Concord School library.

It was at Janet’s house near the Brentwood trolley station that I spent my first “overnight,” a harrowing experience filled with strange noises and fear that her bedroom monsters were less congenial than mine. After we moved from Madeline Street to Baldwin Manor, Janet paid me a surprise visit one Sunday afternoon by walking the three long miles to our house, the badge of a true friend, particularly in view of the spanking she received for her trouble.

Bernice Heinz and Harriet Windeknect lived on Churchview Street near our Methodist Church and a cloister where it was rumored in hushed tones women who had done nothing to deserve such a terrible fate were locked up for their entire lives and never saw their families except through a slit in a door during infrequent visiting hours. Great iron gates guarded the entrance to the cloister. I solemnly studied the gloomy grounds from across the street as I waited for my parents during the interlude between the close of Sunday School and the start of the church service.

My father customarily drove me to Sunday School, then returned home to pick up Mother. This allowed her to wash the breakfast dishes and “do” her hair, a routine that required a lengthy bout with the curling iron. Because she was rapidly turning prematurely gray, she hesitated to go out of the house unless her hair and make-up were impeccable. For this reason, my parents frequently were late to church. This gave me ample time to observe the thick walls of the cloister and ponder untold mysteries about the lives and fate of the women barricaded inside.

Nancy Oliver, another classmate, was one of the many little girls of the era who were blessed with fat, golden curls that bounced like Shirley Temple’s. Nancy, Bernice, Harriet, and Betty Sturm, all friends from school, were guests the following year at my sixth birthday party, which also was attended by my neighbors, Donna Stroud, Audrey Mendlinger, Ruth Emily Lowe, Alice Kracken, Dorothy Lowther, and Herbie Lowther, Dorothy‘s tiny tag-along brother entrusted to her constant supervision after their distraught mother deserted the large family.

For that momentous occasion, my party frock was a plain, practical dress purchased, as were all our garments, in Kaufman’s basement. Most of my guests, however, came attired in the latest Shirley Temple style, party dresses with skirts so full they could be spread like fans. In the snapshots Father took of the assemblage, I am in the background, not in the central place of honor where the birthday child typically reigns. Instead, my guests dominate the front row, spreading their voluminous skirts for all to admire. Mother was embarrassed by the enormous sacrifices their parents surely made to clothe them so beautifully for that event. She was especially mortified when some even arrived with a gift. She had hoped to ease the parents’ minds by stipulating “no present” on the invitation.

Valerie Haas, Marian Post, and Stella Potts were three classmates whose parents suffering through the Depression like most in the community clothed their offspring in drab, practical dresses. I felt especially close to Marian because her mother insisted that she wear long, brown stockings, just like mine. The stockings were a major embarrassment throughout elementary school, but Mother determined to raise me to adulthood would not hear of their removal. Every time we passed an elderly woman whose legs were striated with blue veins, she would nudge me and whisper, “That’s what happens to little girls who don’t keep their legs warm in cold weather.” Her quirky explanations did little to cheer me when most of my friends were permitted to wear anklets in the depth of winter.

During my second year in school (the third grade), Diane Templeton came from Texas. She was tall, blond, and healthy, “a typical Texan,” Mother remarked. I had never before met someone from that storied state, so Diane provided great fascination for me.

She lived in an apartment on the side of the steep hill that led to our church. When I walked up the hill, I leaned forward to avoid falling on my back. Head-first locomotion was essential when ascending Pittsburgh’s hilly streets. The reverse was true during descent. Then I would hold myself back, much as a dog on a leash is restrained, for fear of falling forward and skinning my knees or nose. Those were the only times when I admitted that there was an advantage to wearing stockings. With them, I was not so likely to suffer the consequences of a fall such as those that often befell me on those rare summer days when Mother permitted me to bare my legs to the elements.

Like most of the boys in my class, Ralph Gault was smaller than the girls. He reminded me of a leprechaun in both appearance and his penchant for playing tricks on unsuspecting victims. Only his corduroy knickers and book bag helped him maintain a scholarly air.

For several blocks, our routes home dictated that we walk along Brownsville Road together. Some days, he was congenial, but other times he responded to devilish urges to poke or kick me.

One day, his kick arrived at a moment when I forgot how fragile and polite everyone expected me to be. I kicked him back hard! just as the principal drove by. Astounded by my behavior, she stopped her car to lecture me on the virtues of being a lady. I was too tongue-tied to explain the situation or apologize. Ralph chuckled in the background. After that encounter, I found it hard to look the principal in the eye; no doubt she thought me a very naughty little girl.

Earl Colteryhan was a class member most notable for his sunny face and the difficult spelling of his surname. In time, everyone in the class learned to spell Colteryhan because Earl’s father owned a dairy whose milk trucks bearing the family name plied our community’s streets. Unlike Earl’s family, who lived fairly comfortably throughout the Depression, others in our class were less fortunate.

Alan Duff and Bobby Costello were among my many classmates who came from very poor homes. Mother constantly reminded me to treat them all with great kindness and think of the hardships they suffered. Surreptitiously, I studied them for the “marks of poverty” that Grandmother declared were evident. I saw no special marks on their bodies, but I noted their curious garments. Alan’s ragged shirts, clean by any standards, had been chopped off at the elbow, announcing that he was recycling clothing originally intended for a grown man.

At lunch time, we gathered our lunch boxes or paper bags from the cloakroom and returned to our homeroom desks to eat. When the children spread out the contents of their containers, I quickly observed that both boys had meager options. Bobby who sat directly in front of me turned around each day to inspect my lunch and ask if I had anything left over. Upon losing my appetite at the sight of his perpetually runny nose and unable to down another bite, I always handed over my egg sandwich or banana to him, content that I was “doing my duty.”

I reported each donation to Mother. Although she was pleased to learn that I shared my nutritious lunch with needy classmates, she insisted that I eat enough to maintain my health. Her solution was to send along treats in triplicate for Bobby and Alan. I distributed their portions at the start of our lunch period, thereby avoiding the need to stare at Bobby’s runny nose while trying to savor my own meal.

If my class at Concord Elementary School harbored a glamour girl, it surely was Lillian Urban. In addition to the remarkable ash blond curls cascading down her back always accented by a black velvet bow Lillian possessed the voice of a nightingale. Even at the age of eight, she sounded better to me than Lily Pons, the premiere opera star of the era. Our music teacher, Miss Schneider, seated her students in the order of their musical ability, the best singers in front, those who could not carry a tune in the back corner. What a morale booster it was for me to earn the place next to Lillian!

It never occurred to me to question Miss Schneider’s segregated system, since I was one of the big winners, but shortly after we moved away from Carrick, some of the Concord School parents formed a committee to investigate her treatment of the non-singers. Another complaint they lodged against her was her annual crusade to reveal just prior to Christmas that Santa Claus does not really exist.

Miss Schneider argued that she was a great believer in telling children “The Truth,” oblivious to the fact that her policy ruined many a tiny tyke’s celebration and robbed parents of much holiday joy. Until a concerned citizen brought to light this secret sin of Miss Schneider’s, my parents believed I “figured out” the truth on my own.

For reasons I never quite understood, Pittsburgh Public Schools devoted one day each June to a city-wide picnic at Kennywood Park, an amusement park that represented to me all the joys and terrors of the world of imagination.

Everyone in Concord School talked about the picnic for days before it actually came to pass, even those who could not afford a strip of five-cent tickets for admission to the magical rides. Most, however, made the journey, if only to devour peanut butter sandwiches in the fresh air and jealously eye the more fortunate riders from a distant vantage point.

This was a day set aside for families to get together for picnics, a moment in time when parents and children alike forgot the woes of the Depression. During the days prior to the event, children completed as many household and neighborhood chores as possible in order to earn allowances and save pennies for the strip of tickets purchased from the classroom teachers. Teachers, too, boosted the picnic because the one in each school who sold the most tickets received five extra tickets for her very own use. Without hesitation, the winning Concord School teacher always donated hers to a needy child, giving Mother even more reason to be proud of her former profession.

Mothers formed telephone trees to plan classroom gatherings in the park’s various picnic grounds, and each promised to bring along her specialty, be it baked beans, deviled eggs, hamburgers, cole slaw, brownies, or a large sheet cake. Because Father worked for AT&T and we had free telephone service, Mother was designated as the telephone chairman for my class.

Her specialty was potato salad, a dish that all partakers pronounced the finest they had ever eaten. The day before the picnic, Mother boiled the potatoes and eggs and placed them in the refrigerator to chill overnight. Early on the morning of the great event, Grandmother peeled and sliced the potatoes and eggs and Mother added the ingredients that made (to their minds) the difference between an ordinary potato salad and a culinary masterpiece: sweet onions, gherkin pickles, crisp celery, and pimento.

Mother waited until the very last moment to coat the salad with her secret dressing. Then she packed it in a huge crockery bowl nestled in a basket and surrounded by ice delivered earlier that day by our iceman. Incredibly, the salad remained cool until late afternoon when my classmates and their families gathered around the picnic tables.

Before the lip-smacking picnic, I relished the boat ride through the Old Mill, a dimly-lit, circuitous waterway festooned with rubber spiders, witches leaping from concealed closets, and spooky dioramas. With Father by my side in the boat, I had nothing to fear. Another pleasure was the Caterpillar, an undulating covered ride that gathered speed on its circular track, inviting delighted screams from riders hidden beneath its striped canvas canopy.

Some of my most thrilling moments of terror were provided by Noah’s Ark, a great ship that creaked and rocked ominously on a man-made mountain top so high it could be spotted from afar by folks in cars on the highway approaching Kennywood Park. Clutching my father’s hand, I boarded the Ark tentatively, clambering up the gangplank and moving cautiously through its tricky rooms, most of them equipped with unique secret devices that had to be mastered before we could advance into the next cell. The scariest of all was a set of closely-spaced iron bars blocking the path. My first encounter with the bars gave me the greatest fright of my life to that point, despite my father’s calm assurance that we would escape. To our good fortune, a man just ahead of us figured out the solution: one of the bars was made of rubber. It could be shoved aside, allowing just enough room for one person to squeeze through. Once I knew the trick, I looked forward each year to the perilous journey through Noah’s Ark, but my overweight friend, Donna Stroud, never entered it because her classmates jeered at her size and warned that she would be stuck inside for the rest of her life.

(Donna, another “only” child, typical of the day, was the victim of parents like mine who were terrified at the thought of losing their child. In her case, germs were not the target. Appalled by the birdlike arms and legs of most youngsters of the day, resembling little more than bones wrapped in fleshless skin, Donna’s family was on a campaign to prevent their child from wasting away. Unlike most residents of Madeline Street, Bill Stroud, had steady employment with Nabisco. His salary, together with company donations of left-over products, contributed to the family’s pantry. It was stocked with items most of our neighbors regarded as luxuries. Consequently, Donna’s mother Sara and her Grandmother Sorg spent most of their days in the kitchen preparing hearty entrees and baking cakes and pies that filled the neighborhood with delectable aromas. Donna was required to finish every morsel on her plate.)

Kennywood Park had dozens of other intriguing rides, most of which I watched rather than ride because we could not afford many tickets. There was also the fact that Mother had the premonition of a disaster.

Her prophecy was confirmed shortly after one of our Kennywood Park visits. The Pittsburgh Press ran a news item about a young mother who took her infant on the roller coaster. Unable to breathe during the high-speed dips and loops, the baby died before the end of the ride.

“What did I tell you!” Mother cried. Grandmother clucked her tongue in dismay at the young mother’s foolish decision to put pleasure before the safety of her infant.

The rigors of the Depression taught me to be grateful for my limited number of rides at Kennywood Park. Like my classmates, I received as much pleasure sitting on a park bench and counting the revolutions of the Ferris wheel or the death-defying dips of the giant Jackrabbit roller coaster as I did journeying through the Old Mill’s spooky passageways. One special treat was the delicious cherry popsicle Mother allowed me to purchase at mid-day. A single stick was a mere penny, but when Father slipped me an extra cent (as he often did), I purchased a twin bar that lasted twice as long if I maintained a furious program of circular licking.

At the close of the day, after every morsel of the picnic suppers had vanished, we children played on the swings, slides, and seesaws until our parents packed away the empty containers and checkered tablecloths. Like as not, I fell asleep on the ride back home, lulled by the hum of the car tires over the brick streets of Homestead, the eerie whistles of freight trains on tracks that paralleled the road, and the singular sounds emanating from the brilliantly glowing steel mills.

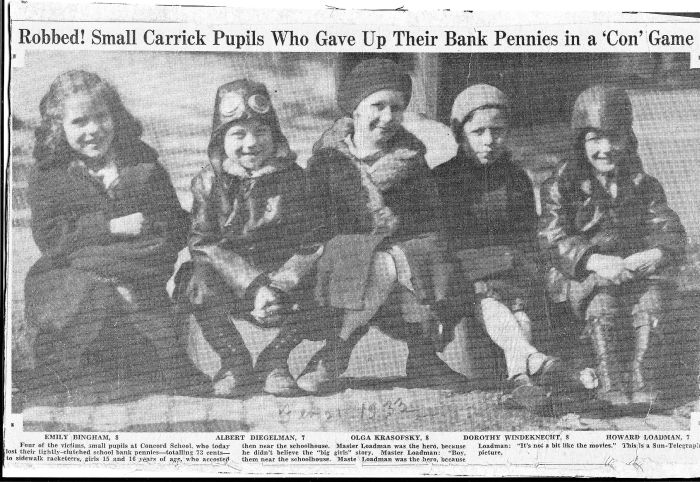

Newspaper article about Concord students who were swindled.

Concord Students crossing the street - note no traffic signals, just a crossing policeman.

A description of the children in the photo by Emily Prichard Cary along with a description of childrens' lives at that time -

The photo of the five children shows Dorothy Windeknect, the sister of my classmate Harriet Windeknect. Somewhere I have photos of my 6th birthday party with all the little girls (except me) lined up in the front row holding the skirts of their party dresses out so far they looked like an array of fans. I believe it was a Shirley Temple style. My outfit was not so elaborate. Mother always bought me the brand of Shirley Temple dresses (a pumpkin on the tag) sold for $1.00 in Kaufmann's basement. She made friends with one of the clerks (she made friends with everyone she met) who each fall or spring would send us all the new Shirley Temple dresses on approval. Mother chose the one or two to do me for the season, and returned the rest in the Kaufmann's truck. That's a service you don't find today.

Harriet Windeknecht was one of the girls attending that party, along with Bernice Heinz (she and Harriet lived near each other on Church Street), Nancy Oliver (lived in an apartment on Brownsville Road near Concord School and not far from a store that sold penny candy), Betty Sturm (lived on Hornaday Road), Donna Stroud (next door), Valerie Haas, Audrey Mendlinger and Ruth Lowe (all behind us on Scout Street) and Dorothy and Herbie Loether (spelling later changed to Lowther) from the larger yellow brick house across the street. Dorothy and Herbie were true survivors. There were nine Lowther children. The oldest girl was very beautiful and sang with a band evenings at the William Penn Hotel. Herbie was the youngest. Since I was between Herbie and Dorothy in age, I played with them both. Dorothy was assigned the job of caring for Herbie, which she did admirably, buttoning his coat, wiping his nose, putting on his galoshes, etc. They had had no mother for several years because their first mother left, so each child was responsible for another. Grandmother observed the departure of the original mother soon after we moved to Madeline Street and often reminisced about it. Even though she was deaf, she understood what was happening from the woman's facial expression and gestures. After hitting her husband over the head for several minutes, she jumped into a taxi. That's the last time anyone on the street saw her. Grandmother's sharp eyes had detected trouble some time earlier. She just shook her head and said, "No wonder the poor woman lost her mind with all those children to care for." Several years later, Mr. Lowther was remarried to a lovely woman who took the children to her heart and made certain that Herbie was always clean and neat without a runny nose. Mr. Lowther was a builder. Before we left Pittsburgh, his business had revived, enabling them to build a lovely home near the South Hills County Club. Soon after it was completed, they invited us to see it. Mother never stopped raving about it. The interior was beautiful, but I fell in love with the yard. The centerpiece was a magnificent Japanese garden with bridges crossing a pond filled with goldfish. I've often wondered if they retained the Japanese theme after Pearl Harbor.

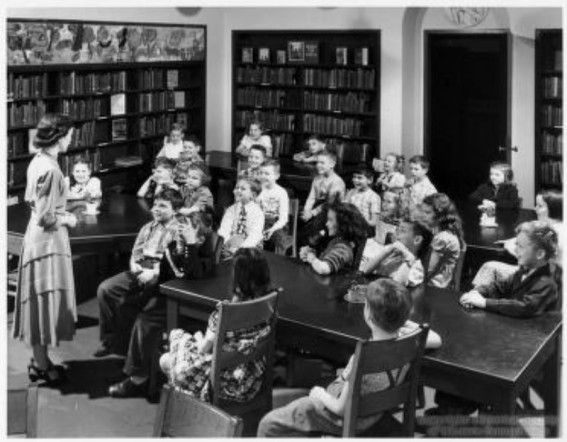

Concord Elementary School Library 1950

Concord Music 1960

School Web Site

This entry was posted on the Pittsburgh Board of Education web site on Friday, October 9th, 2009 at 3:51 pm and is filed under Good News, Pittsburgh Concord K-5, Pittsburgh Grandview K-5, Pittsburgh Roosevelt PreK-5.

Students of Pittsburgh Concord , Pittsburgh Roosevelt and Pittsburgh Grandview get a visit from author Betty Tatham

Award-winning children’s author brings a blast of the Antarctic to the third graders at Pittsburgh Concord, Pittsburgh Roosevelt and Pittsburgh Grandview. Students from all three schools had the opportunity to meet Mrs. Betty Tatham, author of “Penguin Chick,” a story in the third grade Treasures anthology. She shared the processes involved in writing and having her books published. The children went on a virtual tour of an African Safari as they viewed photographs of the animals she studied for her books. Mrs. Tatham wowed the students as she read aloud her story entitled, Baby Sea Otters. Finally, third, fourth and fifth grade students from each school were invited to attend an evening workshop at Pittsburgh Concord with Mrs. Tatham. Parents and students had the opportunity to enjoy more stories by Mrs. Tatham and to create a collage similar to the illustrations in her book, Baby Sea Otters. Ms. Susan Barie, principal of Pittsburgh Concord, provided the students with Sea Creature stickers and theme-related prizes. The students truly enjoyed meeting and working with Mrs. Betty Tatham!

Concord Elementary students learn about Carrick history

Third grade students from Pittsburgh Concord K-5 visit the site of John M. and Harriet Duff Phillips home on Brownsville Road.

Third grade classes of Pittsburgh Concord K-5 greeted Julia Tomasic and John Rudiak of the Carrick-Overbrook Historical Society on Wed., May 25, to learn more about one of Carrick famous residents.

The lecture, held in the school auditorium, was to be about John M. Phillips and his role in local and Pennsylvania history but gradually turned to all local history. The afternoon began with a tour of the original homestead of John M. and Harriet Duff Phillips located next to the school, currently the site of St. Pius X Catholic Church.

All that remains is the original stone wall built in 1890, which the children excitingly touched and patted; amazed it is more than 120 years old. After the tour, a slide show illustrated how Mr. Phillips improved coal mining and showed how Carrick is located above old coal mines.

The students learned how Mr. Phillips helped create Pennsylvania state parks, including Cooks Forest and Pymatuming, the Pennsylvania State Game Commission to regulate hunting and fishing, and the Boy Scouts of America. He was also a director of South Side Hospital. Pittsburgh Phillips K-5 in South Side is named after Mr. Phillips and his wife, Harriet Duff Phillips. However, the children were most interested in the animals and birds, including a kangaroo, which the Phillips kept at their home.

Unexpectedly inquisitive, they were excited their school is the fifth building to carry the name "Concord Elementary" and that the current building dates to back to 1938, built with the help of Harriet Duff Phillips. With all the original lighting fixtures, stage and seating, the students curiously asked about former students, many realizing for the first time their own parents and grandparents may have sat and had classes there.

At the end of the lecture, postcards illustrating Carrick’s history were distributed with invitations to all to come to the Community Cornfest on August 21 in the park named after John M. Phillips.