Milton Hays

Contents

- 1 BIRTH OF THE PITTSBURGH AND CASTLE SHANNON RAILROAD

- 2 EARLY BUSINESS AND SOCIAL LIFE

- 3 Double Gage

- 4 By N.A. Critchett

- 5 Two Railroads Struggling for Supremacy

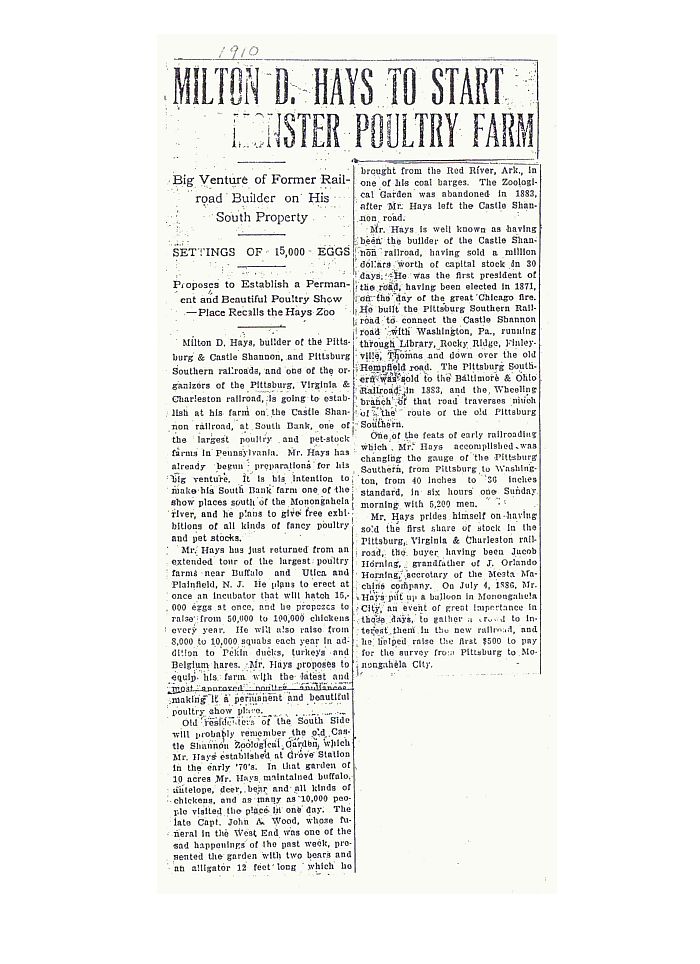

- 6 Both Have the Same Man as President

- 7 In 1910 Milton D. Hays set to open poultry farm

- 8 Reflectorville P & C.S. Railroad Bridge on Edgebrook Avenue near Saw Mill Run Boulevard (State Route 51)

BIRTH OF THE PITTSBURGH AND CASTLE SHANNON RAILROAD

Carrick’s most famous resident was John M. Phillips and Overbrook’s was Milton D. Hays. Milton was born in 1844. He was the son of Jacob and Jane Updegraff Hays. He left home at the age of sixteen. At 22, he was elected director of the Farmers and Mechanics Bank on the South Side and later became the bank’s Vice-President. Mr. Hays resided in the South Bank area of Fairhaven. In 1863, he again left the area for California, passing a year there, and returning to Pittsburgh to take an interest in his father’s lumber business on the South Side.

When Milton Hays was just 27 years old he organized and became the first president of the Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon Railroad. On July 4, 1866 mass meetings were held in Finleyville and Monongahela to get support for the railroad project. To attract a crowd, balloon ascension was carried out. Following the flight, citizens gathered in the town hall to hear plans for the railroad to be made public. In an article written for The Dispatch, Mr. Hays recalled that when he and Captain Thomas Briggs were driving from South Bank to Monongahela for one of the mass meetings, they passed the farm of Jacob Horning (now the property around St. Norbert Street), and he asked them where they were going. “We are going to Monongahela to start a fund to build a railroad right down through your meadow”, the two men said. They asked him if he wanted to buy some stock. The farmer replied that on Saturday he sold a load of hay for $50, and that he would give them two loads for two shares of stock. Whereupon, Jacob Horning, of Fairhaven, became the first stockholder of the new railroad.

The company was incorporated in 1871. The Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon Railroad had a stormy and relatively brief existence, but was very important in the early expansion of the Fairhaven community. Although its creation was for the sole purpose of transporting the coal which it mined from the area to the markets at Pittsburgh, the company’s charter required that it likewise provide passenger service. Initially, the company constructed a six mile long, 40 inch gauge track from Carson Street in Pittsburgh to Castle Shannon. Railroad cars were transported from the South Side by way of the Castle Shannon Incline.

Because its charter required the company to provide transit service, the Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon Railroad entered into the business of real estate and developed a hilltop above the railroad right-of-way and named it Fairhaven. A Pittsburgh Evening Chronicle article dated April 17, 1872, states that 60 lots, formerly owned by F. Briggs, would be offered for sale on April 27 at one o’clock, placing them within reach financially of all. Prospective buyers would need ten percent and five dollars thereafter, with interest. Plans of the lots were on display at the company office. It further stated that the company was offering these lots for their workmen and those who desire to locate conveniently to the new mines. Mining operations were rapidly converging on this area and Fairhaven was to be for years to come the central point of this mining district.

Around this same time, camp ground meetings were established at Castle Shannon. It all began in 1874, when a group of Pittsburgh Methodist Protestant ministers and laymen met to discuss the advisability of purchasing property for a camp meeting ground. Milton Hays, president of the railroad proposed to sell the association 10 acres of land for $5,000. Acres of farmland were purchased and the Castle Shannon Camp Meeting was formed. Later the name was changed to the Arlington Camp Meeting Association. The early association had very strict rules. No dogs were permitted and no smoking within the circle of the tabernacle. People came by way of the Pgh. & Castle Shannon Railroad through Fairhaven. Trains ran every thirty minutes from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m. The fair was 35c for a round trip.

In spite of offering inexpensive lots and a way to get to their place of worship, the railroad did not take an upward turn and it was decided to create an amusement grove at Castle Shannon. The Zoological Gardens of Castle Shannon was established by Memorial Day in 1872. A Professor Bagley, a graduate of Mt. Union College and a native of the island of St. Helena, and whose grandfather was the keeper of the exiled Napoleon, was induced to come to Castle Shannon to take charge of the Zoological Gardens. He was a noted lecturer and used his talents to draw people to the area. He traveled from school to school gravely impressing on the students that the animals that he was telling them about were found at the Gardens. The bait was swallowed and the young people had their parents bring them to the gardens on Saturdays and Sundays the railroad took in the fares.

As the Camp Meeting grounds, the Zoological Gardens and the building of homes expanded, the saw mills in and around Fairhaven flourished. Among the thousands of rare curiosities to be found in the museum on the grounds of the Zoological Gardens on July 3, 1877 were: A lock of hair cut from Napoleon Bonaparte by the person that nursed him, the only picture of Napoleon as he lay in state at Longwood, St. Helena, a cane cut from the hedge around his tomb, a piece of his coffin and of the plaster from his room in which he died. Over one hundred varieties of animals were housed at the Castle Shannon Zoo. In August of 1876 two porcupines, one white groundhog, one raccoon and three pheasants were added.

In 1881, a man by the name of Perry went to the camp meeting at Arlington and was converted. He thought it would be nice to have a church or Sunday school in Fairhaven, so he organized a Sunday school in the old school building. The church got so strong on temperance that they were forced to leave the school building. Mr. Perry carried the organ home on his back. Mrs. Thompson, who lived above the archway on Frederick St. (Glenbury), gave the congregation enough property to build a church in 1890. Edward Provost and a Mr. Dilla worked on the church as carpenters and some of the young ladies of the town helped to drive the nails. The church was known as the Fairhaven Methodist Protestant Church. In 1907 a new church was built on the same site it occupies today.

EARLY BUSINESS AND SOCIAL LIFE

Eventually, Milton Hays wanting to expand the railroad line to Washington, Pa. and Morgantown, West Virginia, created another rail company called the Pittsburgh Southern. At the stockholder meeting on August 1, 1878, Hays was chastised that operating the second company was a conflict of interest with his role as President of the Pgh. & Castle Shannon. Two weeks later, Hays resigned in return for having the conflict of interest charges dropped. As a result, the subsidiary broke away and the Pgh. & Castle Shannon saw its holdings go into receivership from 1879 to 1880. At the zenith of its success during the late 1880’s the railroad ran 23 passenger trains per day along with the many coal deliveries it made to the marketplace at the top of the Castle Shannon Incline. In 1900, Robert McDonald Lloyd of the Pittsburgh Coal Company arranged the buyout of 7,756 of 9,628 shares of the P&CS stock—80% of the railroad. The new controlling interest gutted the P&CS. It assumed operation of the mines, transportation of coal to market and the passenger service. On August 25, 1905, all property pf the P&CS was leased to the Pittsburgh Railways Company, the forerunner to the Port Authority.

Among early businesses in Fairhaven were the gristmill, a saw mill, the Fairhaven Post Office, Galley’s General Store, Brawdy’s Grocery Store, Carcella’s Butcher Shop, Clara Fish’s Dry Goods Store, Muelhorn’s Bakery, Bakey’s Auto Repair, Luffy’s Bowling Alley, and Provost Lumber Company. A cigar factory briefly operated in Fairhaven at the railroad station.

Community life for resident railroad worker spare time, many would entertain themselves at any one of the many saloons in town, dance at the ballroom or visit one of the three brothels in Fairhaven. Residents of neighboring communities nicknamed Fairhaven “Hell’s Hole” in response to what they considered the “immoral behavior” occurring at these popular nightspots. The fire company sponsored carnivals annually and there were many plays performed by budding actors and actresses of the community on weekends.

Double Gage

By N.A. Critchett

Two Railroads Struggling for Supremacy

Both Have the Same Man as President

It was a strange situation-two railroads were fighting each other tooth and nail; and the same man, Milton D. Hays, was president of both! One was the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon, a six mile line serving the coal and steel capital of America. It extended from one of the South Side Hills of Pittsburgh, Pa., to Castle Shannon, a suburb. There it connected with the Pittsburgh Southern, running to Washington, Pa., which was really a glorified spur line of the P&C.S.

This extension, the Pittsburgh Southern, was thirty miles long, while the main line was only six. The contrast probably suggested Abraham Lincoln’s remark about a nine foot whistle on a six foot boiler to the directors of the P&C.S. Anyway, they gave much thought to this matter, and were exceedingly envious of the prestige and popularity of their southern rival. Finally they decided to do something about it.

But what could they do? They had neither ownership nor control of the Pittsburgh Southern, Milton Hays had built that road himself without calling upon the P&C.S. for any kind of financial assistance. The Pittsburgh Southern was serving a rich farm country; the local farmers had capitalized it, at the personal solicitation of Mr. Hays, and the six-mile connecting road had nothing to say about its operation.

It looked as if the P&C.S. directors were licked at the start. However, the Hays railroad owned no motive power or rolling stock; it borrowed such equipment from the northern rival. President Milton D. Hays of the P&C.S. made out the lease to President Milton D. Hays of the Pittsburgh Southern, and both presidents were eminently satisfied.

For a while this arrangement worked beautifully. The Pittsburgh Southern continued to rake in the money of farmers who shipped agricultural products and traveled by rail to the Smoky City and who ordered manufactured goods from the city for use in the country.

And then one bright May morning in 1878, the directors of the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Railroad struck what they thought would be the death blow to the Pittsburgh Southern Railroad. In a formal letter they announced to Mr. Hays that no more P.S. tickets would be honored by the P&C.S. and that the lease of motive power and rolling stock was terminated, both rulings to go into effect at the end of thirty days.

Further than that they could not go, Mr. Hays would still be president of the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Railroad through his influence with the men of wealth who had financed the construction of that road; but he was no longer permitted to use the P& C.S. equipment on his private line. It was a neat scheme to force him to turn the thirty-mile railroad over to the little P&C.S. at a bargain price, for the chief value of the Pittsburgh Southern lay in the fact that it could transport men and goods from the farm lands into the big city. If the thirty-mile road ended in a hayfield six miles from Pittsburgh, it wouldn’t be worth very much as a freight or passenger carrier.

The P&C.S. directors exulted as they planned. They rubbed their hands with glee. At last they had Mr. Milton D. Hays where they wanted him.

But Mr. Milton D. Hays was not the kind to lie down and let the wheels of fate roll over him. The very day he received the board’s notification, he called upon a financier by the name of Father Henrici, head of a cult known as the Economite Society.

The Society owned and operated the little narrow-gauge Saw Mill Run Railroad. Mr. Hays had known Fr. Henrici for years, and although the two men were not reputed to be on friendly terms, Hays offered a proposition which the Economites were glad to accept.

Under the terms of this agreement, Hays would outwit the greedy directors of the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Railroad. To Father Henrici he explained the whole situation. “They’re squeezing me to the wall,” said Mr. Hays. “Severing my road from the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon and leaving me in the middle of nowhere without motive power or rolling stock”.“What does that mean to the Economite Society?” Father Henrici asked cannily.

“Just this,” came the reply. You lease me a right- of -way over the tracks of the Saw Mill Run Railroad. I’ll pay you a fancy price”—he named a tempting figure—“and that will give me entrance to Pittsburgh. Then I’ll connect with Castle Shannon, my northern terminus, by laying three miles of track; and I’ll have a complete line all the way from Washington, Pa. to Pittsburgh without being bothered by the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Railroad. However, I must get this down within thirty days.”

“But,” questioned Father Henrici, “how can you use the Economite Railroad with its thirty-inch gage, while your road has a forty-inch gage? “Easy. We’ll lay a third rail.”

“And what will you do for rolling stock?"

“You leave that to me,” Hays smiled reassuringly. “I’ve already started to do something about that. And in the meantime,” he cautioned the Economist leader, “not a word of this to anybody outside of your Society.”

Father Henrici pledged himself to secrecy. The lease was signed the following morning. Milton D. Hays was elated. Right now he held the ace cards. As president of the P&C.S. he was legally entitled to sit in on all the meetings of the board of directors, and thus he could keep informed on what they were doing, while they had no means of learning the plans of the Pittsburgh Southern Railroad. Meanwhile, he could still use the P&C.S. motive power and rolling stock, under terms of the lease which would not expire for nearly a month.

But Mr. Hays was confronted with a serious obstacle. In 1878 the P&C.S. and the Pittsburgh Southern were almost the only two railroads in the country-indeed in all the world-which had forty-inch gage. The P&C.S., originally a coal road, had been made especially to coincide with that gage, and when the Pittsburgh Southern had been built it naturally followed the same gage as the road it connected with.

“Which means,” Mr. Hays thought ruefully, “I’m going to have a pack of trouble getting motive power and rolling stock on short order.” It was only too true. Ready-made engines of forty-inch gage could not be had for love or money, although Mr. Hays appealed desperately to all of the builders in the East. Not one of them had such an engine on hand, but all were willing to manufacture as many forty-inch engines as he could pay for, if only he’d give them time.

But time was mighty important to the hard-pressed railroad builder. Since he could not buy a forty-inch locomotive on short notice, and since his roadbed was not heavy enough to carry a heavier type, he succeeded in locating a twenty-four ton locomotive of thirty-six inch gage which the Pittsburgh Locomotive Works agreed to sell to him for $4,500.

He bought it. Then, looking around for rolling stock to fit such power, he found a small three-foot gage line in northwestern Pennsylvania and quickly made a deal with them for two passenger coaches, one baggage car, and three flat cars. Buying these, he exacted a pledge of secrecy and ordered the equipment to be relettered with the name Pittsburgh Southern.

While this was being done, progress was being made on the work of grading for the three miles of railroad to be built between Castle Shannon and the terminus of the Economites’ Railroad. This work was pushed with the use of the P&C.S. equipment, which under the still unexpired lease the Pittsburgh Southern was permitted to use. The P&C.S. directors fretted and fumed but could not do anything to stop the work.

It annoyed those directors considerably that they could not penetrate the plans of Milton D. Hays. They knew nothing of the deal he had made for the Saw Mill Run right-of-way; in fact, it was commonly believed that the Economites were hostile to Mr. Hays. So no clue could be gathered in that direction.

They laughed at Hays for building what they thought was a blind road, three miles from Pittsburgh, just as Noah’s neighbors laughed at Noah for building the Ark. But Hays did not give away his hand as Noah did. He let it known that he had great faith in the future growth of the City of Pittsburgh, and that he would probably run a stagecoach line into the city until it grew to meet the end of his railroad.

When this news got around, most of Hay’s friends and enemies decided that he had gone out of his mind. Nevertheless, the railroad builder kept persistently at his task. Four days from the expiration of his thirty-day period of grace he sent this message to the Pittsburgh Locomotive Works: “Rush that locomotive. I’ll make the road fit it. Don’t do anything but hurry.”

Another message was sent to the road from which Hays had purchased the rolling stock, telling them that he was ready for those cars. The P&C.S. directors and their spies kept prowling around Mr. Hays and his operations, but so far they had learned next to nothing of his intentions, although they suspected he had some deep dark scheme up his sleeves.

Finally the last spike was driven connecting the Pittsburgh Southern with the Saw Mill Run Railroad, and on a Sunday morning, the day before the thirty days was to expire, the P&C.S. directors emerged from church to see Hays and his gangs of workmen changing the gage of the entire length of his railroad to fit his newly acquired locomotive and cars! At the same time the P&C.S. forces were amazed and chagrined to see that the Hays men were spiking down a third rail parallel to the Economites line, permitting three-foot gage equipment to roll over the tracks, as well as the Economites’ thirty-inch power and cars.

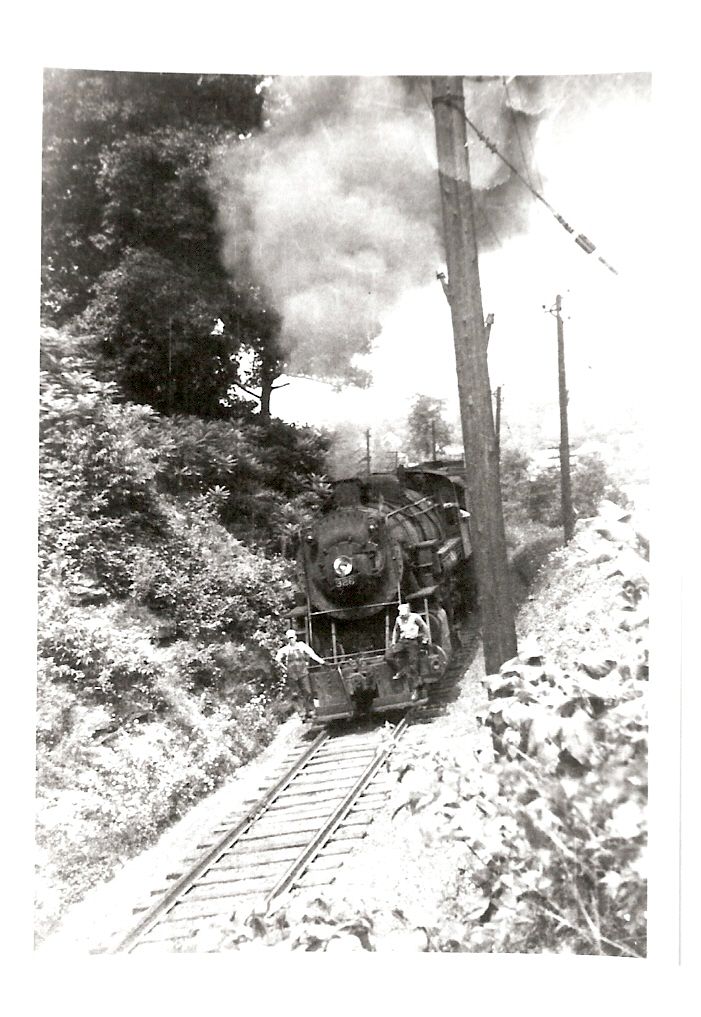

Hays locomotive had been brought to the tiny Saw Mill Run station on a low flat truck pulled by eight powerful brewery horses, a fire was built in her boiler, and soon she was on the track, pushing ahead of her a car of rails and other necessary material for the workman.

In short time she reached the end of the Economites’ road at Banksville and was on the three-mile extension of the Pittsburgh Southern en route to Castle Shannon, the junction point.

The Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon men were furious. They realized that their contract with Hays would not expire until Monday midnight. It was now Sunday and they would have to do something to block their rival before the courts opened on Monday, on which day they might hope to obtain an injunction.

Coming out of church, the directors, headed by a man named Pierce, held a hasty council of war. They realized that two sets of track changing gangs in the employ of Milton D. Hays were rapidly nearing Castle Shannon, one from the north, the other from the south, but neither gang had yet arrived at that point.

Hays had already returned all of the P&C.S. rolling stock and power, in order to clear his own road for the change of the gage. The directors’ forces induced Matt Rapp, their master mechanic to get up steam in one of the engines and run her out onto the main line, while other men would spike the switch and thus block the Pittsburgh Southern workmen.

The P&C.S. men went even further. They lifted a rail so that the engine would fall into a culvert—gently, so as not to be damaged. This, they decided, would block their rivals even more effectively.

But it didn’t. A few minutes later came the Hays engine over the hill, brightly painted and lettered with the words “Pittsburgh Southern.” Her shrill whistle shattered the quiet the quiet Sabbath air. The track laborers were working industriously ahead of her.

When this locomotive reached the one which had been ditched, Hays did some quick thinking. He had his men connect the two with chains. Then he forced his way through an angry gesticulating group of P&C.S. men and climbed into the cab of his engine, brandishing a long-handled wrench.

“Get off the track,” he bawled out, “If you don’t want to be killed!”

Then with a yank and a jerk, and with the aid of a re-railing frog, he got the P&C.S. locomotive back on the track. A short distance further on, the track had been torn up; its edges were perilously near a steep embankment. The Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon forces had done everything they could to make it difficult, not to say impossible for Hays and his men to complete the change of gage within the specified time.

There was only one way to clear the track, and Hays did it. Disconnecting his rivals’ engine he gave her a powerful shove with his own motive power, so that she fell down the embankment, down to the rocks below, a battered steaming mass of twisted steel.

Matt Rapp, the P&C.S. master mechanic, uttered a cry of rage and heaved a hammer at Mr. Hays. It hit a glancing blow, knocking him unconscious. That seemed to have been the signal for a free-for-all fight. With weapons and burly fists, the P&C.S. men exchanged blow for blow until their opponents finally drove them off the field. Such was railroading in the year of our Lord, 1878.

By the time Mr. Hays recovered consciousness his entire railroad was consolidated and changed to three-foot gage from Washington to Pittsburgh. It was a spectacular triumph, and the Pittsburgh and Southern employees further desecrated the Sabbath by giving vent to loud and prolonged cheers, to which was added the penetrating shriek of their one and only locomotive whistle.

That ended the Castle Shannon war. The following day, which was Monday, Milton D. Hays resigned from the presidency of the six mile rival, to devote his entire attention to his own line.

And that finishes the story, except that, years later, both roads were finally taken over by the great Baltimore & Ohio System.