Neighborhood Authors

Contents

- 1 This section is an ongoing compilation of written works by neighborhood writers who have had their work in the media.

- 2 The Next Page Shining a light on traffic signals

- 3 The Next Page: Shining a light on traffic signals Want to save gasoline? Of course you do. Pennsylvania deserves a better way to coordinate traffic signals -and keep the traffic flowing

- 4 Sunday, August 05, 2007

- 5 By John J. Rudiak

- 6 Next Page: Nearly everything you don't know about traffic signals

- 7 Sunday, August 05, 2007

- 8 By John J. Rudiak

- 9 Storytelling: My pal Red loved ducks, and they knew it

- 10 Wednesday, October 31, 2007

- 11 by Joseph Krynock

- 12 Holiday Musing: Special fruitcake has served family for generations

- 13 Tuesday, December 01, 2009

- 14 By Mike Woshner

This section is an ongoing compilation of written works by neighborhood writers who have had their work in the media.

The Next Page Shining a light on traffic signals

The Next Page: Shining a light on traffic signals Want to save gasoline? Of course you do. Pennsylvania deserves a better way to coordinate traffic signals -and keep the traffic flowing

Sunday, August 05, 2007

By John J. Rudiak

Drawing by Stacy Innerst, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Drawing by Stacy Innerst, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

It's no secret that Pennsylvania is a maddening patchwork of tiny municipalities that breed inefficiency. But here's something you probably did not know: In Pennsylvania, traffic signals are owned and operated by the municipality in which they are located. Most citizens would assume, if they have thought about it at all, that PennDOT owns the signals. For most municipalities, signal maintenance is a low priority. It usually consists of assuring that the lights turn green, yellow and red. Efficiency as part of a complex and interdependent traffic system is not a consideration. The repair of detectors -- the devices that activate a green light when a vehicle approaches -- is one of the key components to improve efficiency. But for many towns, it is an unnecessary expense.

With fuel over $3 per gallon, these are expensive times for motorists. Every minute delayed at inefficient or malfunctioning traffic signals means money wasted.

For a driver in Pennsylvania, it seems like getting two or more green lights in a row is a major achievement. Everyone is becoming aware of our antiquated system of traffic signal management -- and the learning process is through the wallet.

In our land of fragmented governmental entities, development is often willy-nilly, approved by a municipality with little regard for the larger fabric. Traffic congestion is one of the first ill effects. Irate motorists complain to PennDOT, not to the towns that caused the problem. Developers must be held accountable for the traffic they generate and be responsible for the traffic signals that benefit their developments.

PENNDOT'S DISTRICT 11 COMPRISES Allegheny, Beaver and Lawrence counties. The district has about 1,700 traffic signals, 650 in the city of Pittsburgh alone. It's difficult to believe but there are dozens of signals installed as early as 1938 -- and are operating as built over 65 years later. These signals have never been reanalyzed or updated.

The Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission is recognizing that signal maintenance and modernization must be a priority. Only five or six municipalities were recognized as having a long-term transportation plan; most do not.

In the 1980s there were several PennDOT programs reconstructing dozens of signalized corridors. The traffic signals on routes 8, 30, 51, 88, and 65 were reconstructed and promptly turned over to the respective communities. Sometimes they were maintained, but usually not. In addition, the corridors have never been reanalyzed -- meaning the original timings have never changed for over 15 years.

If one traffic signal costs, on average, $100,000, millions of dollars have been spent to rebuild these signals. The most important item joining all of these municipalities, rich or poor, is the capability to maintain them.

Traffic signal coordination through dozens of adjoining municipalities is a task for a central administrator. PennDOT has tried to assume this role in District 11 and other parts of the state. But one cannot coordinate signals along a corridor if one or more of the municipalities involved do no signal maintenance.

Traffic flow is like water in a pipe. If one section fails and is not repaired, water will not flow regardless of the condition of the adjoining pipes.

This is the same situation on our major arterials. When vehicles are restricted through a corridor, the system fails -- resulting in bottlenecks and irate motorists. The lack of a central supervisor and enforcement of the systems' maintenance and timing changes leads to even more congestion and gridlock.

Are the municipalities really to blame? Their high priorities are fire and police, water, sewers and very basic municipal services. When these suffer, local taxpayers complain. Can the efficiency of signals be a major concern?

SO, HOW CAN WE IMPROVE the traffic signals and systems of Pennsylvania?

The state should create a special section in each Engineering District Traffic Unit to evaluate and implement new timings periodically on all corridors. If this is done, the state must also have a method of forcing towns to maintain and update their traffic signals.

Yet demanding that towns maintain signals without adequate funding will force the state into limited signal ownership. The state does not want to own the signals -- but is inevitable.

We must begin to investigate how other states are operating and how signal responsibility is assigned. There is no need to invent a new system when others have already developed policies.

Where will the dedicated funding come from? Whether funding is allocated from existing fuel taxes or new taxes is a decision of the Legislature. But when fuel costs increase daily, will the public notice, or accept, a tax increase? I believe they will only if there is a noticeable improvement in travel times and in the efficiency of all traffic signals.

Unnecessary signals, stop signs, unrealistic speed limits and other traffic restrictions must be evaluated and removed in accordance with law. The state should not be compelled to operate and maintain unnecessary traffic controls.

The present policies regarding traffic signal management in Pennsylvania cannot continue. Motorists must not be satisfied with getting just two green lights in a row. It's time to demand more efficient signals and systems.

First published at PG NOW on August 5, 2007 at 12:07 am John J. Rudiak recently retired after 35 years at PennDOT, where he was a traffic systems control specialist for District 11. He lives in Carrick (jrudiak@yahoo.com).

Read more: click here

Next Page: Nearly everything you don't know about traffic signals

Sunday, August 05, 2007

By John J. Rudiak

The American Traffic Signal Co. claims the first electric traffic signal installation. It is widely accepted as being installed in 1914 in Cleveland at 105th Street and Euclid Avenue. But most historians give credit for inventing the first traffic signal to Garrett Morgan (below), an African-American inventor and businessman from Cleveland and the son of former slaves, in 1923. Other cities also claim to be first, including Detroit and Salt Lake City.

All modern controllers have a signal monitor to make sure that opposing (or "conflicting," as traffic engineers say) signals are not green when they are not supposed to be. We all rely on knowing that opposing traffic will not be given a green light when we have a green light. This signal monitor will detect a failure within a millisecond and put the signal into an emergency flashing mode, whether it be yellow-red, or all red. Not the best operation -- but safer than two opposing green indications.

All traffic signals sold today must be low-energy and low-maintenance light emitting diode or LED indications. Old incandescent signals used bulbs consuming 150 watts per indication, while the new LED type uses only about 10 watts. A typical intersection now uses the same energy that was used to light a single bulb and the indications seem brighter too and last eight times longer. LED signals are now used all over the world.

Early traffic detectors were the "treadle or pressure type" where vehicles rode over a steel plate depressing a contact and sending the signal to the controller. You can sometimes see remnants of these treadle detector plates in the street because they are difficult to remove.

Detectors of various types and methods can be seen throughout the region and world and range from wires in the roadway that set up an electric field, radar, microwave and relatively recently, video cameras that rely on pixel change to detect vehicles. For pedestrians, a simple press on a pushbutton still does the job.

These modern detectors detect single vehicles. They can also count the vehicles over a period of time -- and then transmit this data to a microcomputer, which analyzes it and determine the best cycle length, approach-timing splits and offsets for the system.

Telling the controllers when to turn green or red in relation to the adjacent signals is referred to as the "offset." Turning the next signal green a period of time after another can progress a platoon of vehicles through a corridor at a set speed. This is called a progressive and coordinated movement of traffic.

The time-space continuum in which the platoon travels is called the "greenband." A well-coordinated signal system of a central business district or a traffic route can be a marvelous thing to observe and drive.

Early methods of traffic signal interconnection consisted of copper wires sending electric pulses between signals from a "master" controller. These pulses kept each controller timing drum at the right place relative to the others. Modern interconnection uses fiber-optic cable between intersections and spread spectrum radio which uses frequency-hopping to eliminate radio interference and is becoming more dependable and versatile.

The first installation of fiber-optic cable in 1988 and spread spectrum radio in 1998 in Pennsylvania were in Forest Hills and Dormont, respectively. They are still operating today.

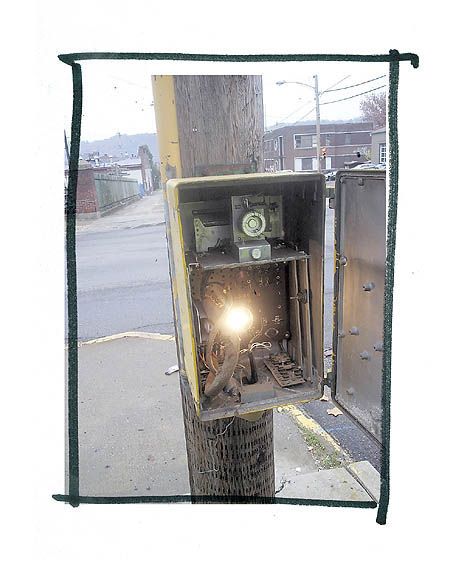

Click photo for larger image. Photo by John Rudiak

Click photo for larger image. Photo by John Rudiak

How does a traffic signal work? How does it switch from green to yellow to red, and back? Very early controllers were simple. They had a timer that works light switches electrically through a motor-driven camshaft. These early controllers began to be installed around 1938 and are still functioning today in many area towns. (The photo at right is an old but working controller in Ambridge.) They can be easily identified by listening for a "kachunk" sound for each indication change as the camshaft turns. Although these early controllers could be "traffic responsive" or "actuated" by vehicles, most were not. They are called "fixed time." These signal controllers could also be "synchronized" by having several intersections in a row turn green at the same time.

On Nov. 3, 1924, Pittsburgh became the first city to employ a full-time professional engineer, Burton W. Marsh, under the title "traffic engineer." Mr. Marsh later served from January 1969 to July 1970 as executive secretary of the Institute of Traffic Engineers. As it happens, the ITE is holding its 2007 annual convention in Pittsburgh -- starting today and running through Wednesday.

First published at PG NOW on August 5, 2007 at 12:08 am

Read more: click here

Storytelling: My pal Red loved ducks, and they knew it

Wednesday, October 31, 2007

by Joseph Krynock

This story is about a friend of mine, who, after he retired, liked to start his days at the edge of the Monongahela River.

James Barry Neiport, better known as Red, fed "his" ducks and geese before sunrise almost every morning. They recognized his car and they would casually swim across the river to meet him. When I could, I met him at the South Side boat dock almost under the Birmingham Bridge. He was always watching for wild birds, animals or fish.

On one morning, I drove up to see him sitting in his car. It was a cold, miserable, rainy, winter morning. Red had his car window halfway down. He was throwing slices of fresh bread out to the ducks, geese and the lonesome sea gulls that had gathered beside his car door.

I ran around his car and got in so we could talk.

In a happy tone of voice, he warmly greeted me with a "good morning." Then he grumpily shouted, "You're late, five minutes too late!"

I knew that he liked to tease people so I waited for him to finish. Then I said, "Late for what?"

He handed me something small and I thought: Why is he handing me a miserable wire tie from a loaf of bread?

He knew from my expression what I was thinking and said, "Nope, you're so wrong, I'll tell you what it is ... It's a duck killer, not just a piece of trash. It's something that kills ducks!"

What was he talking about?

"It's a what?" I asked. "What is wrong with you today, Red?"

"Give it back and I'll show you."

He took the wire from me and put it on his finger like it was a ring. He said:

"Well, five minutes ago, I was feeding these birds and I noticed that one duck was not eating. He was just standing there looking up at me. Then I saw these two wire ends on the top of his nose, beak, or whatever you are supposed to call it. It looked like he was trying to swallow a large bug.

"So I opened the car door slowly and the duck was so close that the car door swung out and went right over him. While all of the other birds backed up and away from the car but he didn't. He just stared at me, looking at me I guess for help.

"So I reached down slowly and picked him up and I put him in my lap. The wire was on his top half of his beak and was blocking his throat. Although he could still pick up bread he could not swallow even when he tilted his head up and back. He probably was picking up bread or other stuff and picked this litter too, the 'duck killer' wire loop by accident."

Red told me how he gently took the wire off of the duck's beak and gently set the duck back down. The duck had sat looking at Red silently for a few minutes and then waddled off to join his flock, glancing back several times, ever so thankful to Red for his help.

This is the first time that I ever saw Red so emotionally disturbed. People who litter and hurt animals in the process brought tears to his eyes.

Red died a few years ago. In lieu of flowers, donations were made to provide for a bench at the South Side boat dock dedicated to Red and friends -- the ducks, geese and his other two-legged companions. His beloved feathered friends live on without Red.

In his memory, those who feed the fowl must remember: Dispose of your trash properly, please.

-- JOSEPH KRYNOCK, Carrick First published on October 31, 2007 at 12:00 am

Read more: click here

Holiday Musing: Special fruitcake has served family for generations

Tuesday, December 01, 2009

By Mike Woshner

For as long as I can remember, a vital part of the Christmas season involved preparing, baking, serving and eating homemade fruitcake that was unlike any other I have ever seen, smelled or tasted.

In this dark and spicy mixture, endless chunks of candied fruit, citron, raisins, and walnuts leave little room for the cake itself. A far cry from the commercial fruitcakes that deserve to be the brunt of holiday jokes, its unique and robust flavor forces you to seek a complementary mouthful of milk or coffee just to settle your taste buds down.

The pleasure of consuming this holiday treat is only surpassed by the pride and satisfaction of creating it. When my father died 11 years ago, I felt like an apprentice who had studied under the master and thought he knew the trade well until suddenly left to create the masterpiece alone.

Dad likely shared the same experience when my grandmother died in 1954. He and his mother made about 25 pounds of fruitcake each Christmas for years, using a huge round antique bread pan (the kind with the cover and vent) as the main mixing bowl and a recipe cut from a Pittsburgh newspaper in the 1930s (my best approximation).

Down through the years, Dad shared recollections of how the spacious kitchen at my grandmother's house on Pittsburgh's South Side (now Mario's) was filled with the sights, sounds and smells of this pleasant task. Dad recalled how they had bought whole candied fruits and citron in large chunks and cut them in little pieces by hand.

When Grandma died, Dad became the master fruitcake baker and was unwavering in his efforts to observe the same process he and Grandma had followed.

The original recipe that my grandmother had cut from the newspaper a half century back was the only one Dad would follow. In the early 1970s, my wife typed up an exact copy in large letters but, despite his failing eyesight, he strained to continue reading the tiny newsprint on the browned, torn, cracking newspaper.

As years passed, stores that sold the bulk citron and candied fruits became scarce and the colorful, appetizing displays were replaced by pre-cut, pre-packaged pieces in convenient, modern, ho-hum plastic containers. Dad reluctantly stopped shelling whole walnuts when his arthritis became too disabling, and I declined to shell them because, "I didn't have time."

I eventually convinced him to buy shelled halves and again refused to cut them up by hand, opting instead to use a food processor. This irked him considerably because a bit of the nutmeats became powdery. In later years, I simply bought packages of small walnut pieces and one package of halves to decorate the tops of the cakes. I'm sure that irked him even more.

When my mother died in 1986, it became a post-Thanksgiving Sunday tradition for Dad and me to make the fruitcakes while following the Steelers on television and figuring out what to buy his grandchildren for Christmas. At first, I was only allowed to perform trivial tasks such as separating eggs and cutting up the fruit into smaller pieces. As years passed and Dad began slowing down, I was given more responsibilities.

The ultimate compliment came when, at age 49 with 15 years of experience, I was finally allowed to fold in the egg whites. Family and friends still recall my jokes about being deemed worthy of this "awesome" responsibility. (A few years back, when I commented that the cakes seemed a bit dry, my fruitcake-loving daughter and apprentice, Lynn, sarcastically remarked, "It was probably the way you folded in the egg whites.")

The last two years that Dad and I made fruitcake together, I did most of the cutting, measuring, mixing and baking. But I was always sure he knew that he was still the undisputed master.

My many memories of Christmas at home have been heightened each of the past 11 Christmas seasons when Lynn and I make Dad's fruitcake for family and friends. It also appears that the obsession with tradition was bequeathed to me, at least during this ritual.

I inherited Grandma's large bread mixing pan and the prized recipe. I have the crisp, clear copy of the recipe that my wife typed out but, in tribute to Dad and in memory of his humorous resistance to change, I strain to follow the fading instructions from the torn, battered, parchment-like newspaper clipping. Maybe someday I'll shell whole walnuts.

Carrick resident Mike Woshner, a freelance writer and trainer/consultant, can be reached at mwoshner1@verizon.net.

Read more: click here